What to do when every job says "tech skills required"

Time to stop thinking of tech as separate from the rest of life

Welcome to Art Science Millennial, a newsletter for non-techies navigating the world of tech! I know the struggle because I’m one of you.

No magic in the air for fresh graduates this year.

It’s graduation season, but what should be a time of promise and new beginnings has been replaced by feelings of limbo and dread. One particular news report about job hunting blues in The Straits Times caught my eye:

Graduates who have been trawling job portals also say they do not see many entry-level vacancies, and some think there is little demand for general degrees such as social sciences and business.

The openings offered under the recent SGUnited Traineeships Programme are helpful, they say, although several think they may not have relevant skills needed.

Says Mr Chua: "A lot of the job opportunities I see need tech skills, which we didn't really learn as a social science student, so that's one disadvantage we have."

Assuming that the sentiment regarding general degrees is true, it’s caused either by:

A reduction in the number of jobs usually filled by general degree holders, or

Jobs usually filled by general degree holders now increasingly demand some form of technical skill.

So which is it? It’s been some years since my fresh grad days, but my experience looking for a job outside journalism tells me it’s the latter.

Many journalists see corporate communications as a handy backup plan if they ever leave reporting. I was no different, thinking that my combination of writing ability, angle shooting, socio-political acumen, and newsroom contacts would make it easy to find a corporate communications job.

Out of the newsroom into the fire

But I soon realised that while there were indeed many comms job openings, a significant number of them were already requiring skills of a different sort. And that shouldn’t have been a surprise, given that enhancing an organisation’s reputation is no longer just about writing press releases and pitching media stories.

Instead, entities increasingly want to communicate through their own content and channels, so familiarity with social media listening platforms, content management systems, and performance measurement tools like Google Analytics are now valued.

And it’s not just comms. When I applied a few years back to be a political analyst at a consultancy (I had fancied my chances as a former political correspondent at The Straits Times), one of the first questions I faced was if I had any experience with data analytics and visualisation.

Yeah, I didn’t get the job.

Now, I don’t want to be an alarmist and give the impression that it’s impossible for general degree holders to find a job. After all, I eventually did two fulfilling years of comms at multi-national corporations. But it’s undeniable that I missed out on quite a few appealing opportunities fresh out of the newsroom because of my analogue skillset.

And judging by the periodic comments I come across on social media, the anxiety among fresh grads about needing tech skills is not insignificant.

Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences graduate feeling the heat.

The Woke Salaryman fields a question about pressure to pick up “in-demand IT skills”.

Like what you’re reading so far? Sign up so you don’t miss the next update of Art Science Millennial!

The graduate quoted in the earlier Straits Times report elaborated in a student website on how his close friend had advised him to pick up coding when they entered university:

Trouble was, I had little interest in programming. I didn't see how it was useful for me. I preferred reading about international relations and history. I could spend all day reading the news and speculate what could happen next.

Looking at him now, I wonder if I should have heeded his advice. Even if I didn't enjoy it, I might have acquired a new skill now and could at least better compete with my peers for a job.

…

The pandemic killed the Luddite in me. I finally decided to download Tableau courses and learn it properly. To be fair, it is not boring. However, it has since been a week since I looked at the courses (partly because I have a part-time job).

This gets to the heart of the difficulty faced by humanities, arts, and social sciences graduates in mastering new tech skills: It’s bloody hard to learn about something that is the complete opposite of our natural inclinations and interests.

I should know. I'm a news junkie, regularly imbibing The New York Times, The Guardian, The Economist, and a whole host of other news outlets. For the longest time, I read everything - except for tech and business articles. My eyes would glaze over whenever I came across those. Geopolitics, international leaders, and elections just seemed so much more consequential to the fate of the world.

You are into tech, you just don’t know it yet

The turning point for me was no eureka moment, but rather a slow drip of realisations that tech has just as much impact on our collective destiny.

Care about speech issues and policies? The biggest fights over freedom and responsibility of speech is playing out on social media platforms.

Presenting… the very first Trump tweet with a warning label.

Passionate about gender equality? Silicon Valley too has an entrenched problem of toxic workplaces.

Outraged by police brutality? Facial recognition technology might make things even worse for ethnic minorities.

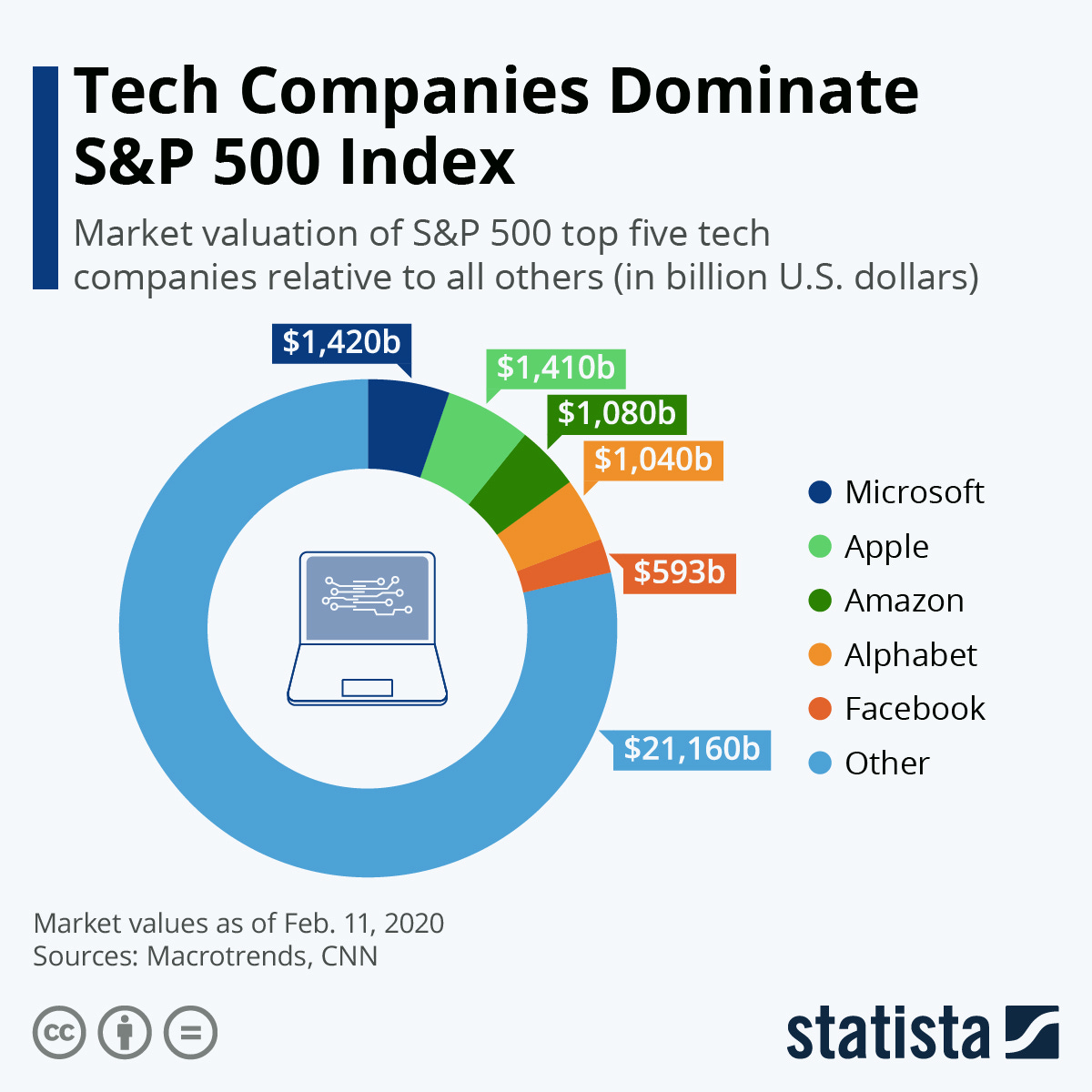

And worried about corporate giants crushing the little guy? The only companies to hit a trillion-dollar market value are tech firms and five tech titans make up 20 per cent of the S&P 500’s market capitalisation.

That’s 495 companies making up just 80 per cent of the value of the 500 largest companies listed in the US.

With tech’s influence on all aspects of life growing, there’s no tradeoff between learning about tech and learning about the world. To me, this mental shift is the crucial first step that should be taken before diving head-first into picking up tech skills. If you’re sitting through a “basics of machine learning” MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) just to get a punchier resume, those hours of video lectures are going to dragggggg. But if you’re concerned about bias in Artificial Intelligence, that same course might not be so painful.

Warming up that tech curiosity

Of course, that is not to say that building up general knowledge about the tech landscape is a breeze, but it’s definitely less of a leap than, say, committing to learning to code in Python. Some of the things I did, and continue to do, were:

Deliberately reading tech and business articles (essential reading because of tech’s outsized presence in business today) and forcing my eyes to “unglaze”. That means finishing the business, finance & economics, and science & technology sections of The Economist before allowing myself to flip to the other parts of the magazine. It’s no fun having to google unfamiliar terms every five lines, but it gets better.

Signing up for useful information streams like The New York Times’ On Tech newsletter.

Reading stratechery.com to understand the business strategy of tech companies. There are plenty of insights about technology’s impact on society too. Oh, and added bonus for me, the writer regularly discusses the media industry as well, a perennial interest of mine.

Channelling a bit of my TV addiction to learning about things. When I’m asked for an example of a computer vision classifier I point them to Silicon Valley. And I have Bobby Axelrod to thank for introducing me to many financial and investment terms.

I don’t want to trivialise the learning of tech skills, or any skills for that matter. I certainly didn't get my first data analytics job by sitting around watching HBO all day. What I'm trying to get at is that we’re more inclined to learn about and stick with something that we’re interested in. And the fastest way for us general degree holders to get interested in tech is to erase that arts/science differentiation in our minds.

And for those in the Class of 2020 who fear that it’s too late to begin getting smarter about tech, I started my tech learning journey almost 10 years after graduation. What I’m going to say next is a cliche, and may even come across as patronising, but is no less true:

The best time to start was yesterday. The second best time is today.

Thank you for reading Art Science Millennial! If you enjoyed this piece, sign up so you get subsequent updates in your inbox!