Election special: Social media, another space the PAP dominates

No longer the underdog's exclusive realm since at least 2015

The general election has just been called, with Singaporeans set to vote on July 10. In my previous life as a political correspondent, I would be on the ground now trailing candidates in the most hotly contested constituencies and covering the polls from a front-row seat.

Instead, during this period, I’ll be combining my past and present to write about the intersection of politics and tech, especially relevant as this will be the country’s very first social distancing election.

When I first started using social media about a decade ago, it was almost exclusively the playground of dissenting voices. I hardly ever came across pro-establishment opinions on Facebook and opposition supporters treated social media as their weapon of choice to take the fight to the powers that be.

Even Low Thia Khiang, Singapore’s longest serving opposition MP, said as much during a 2015 rally speech:

Before we had social media, the mainstream media acted as the mouthpiece of the PAP and was the only source of information.

Now, with competition, people have more means to find out the facts and truth. With education, people can analyse and see issues on their own. We need a system that promotes such progress in society.

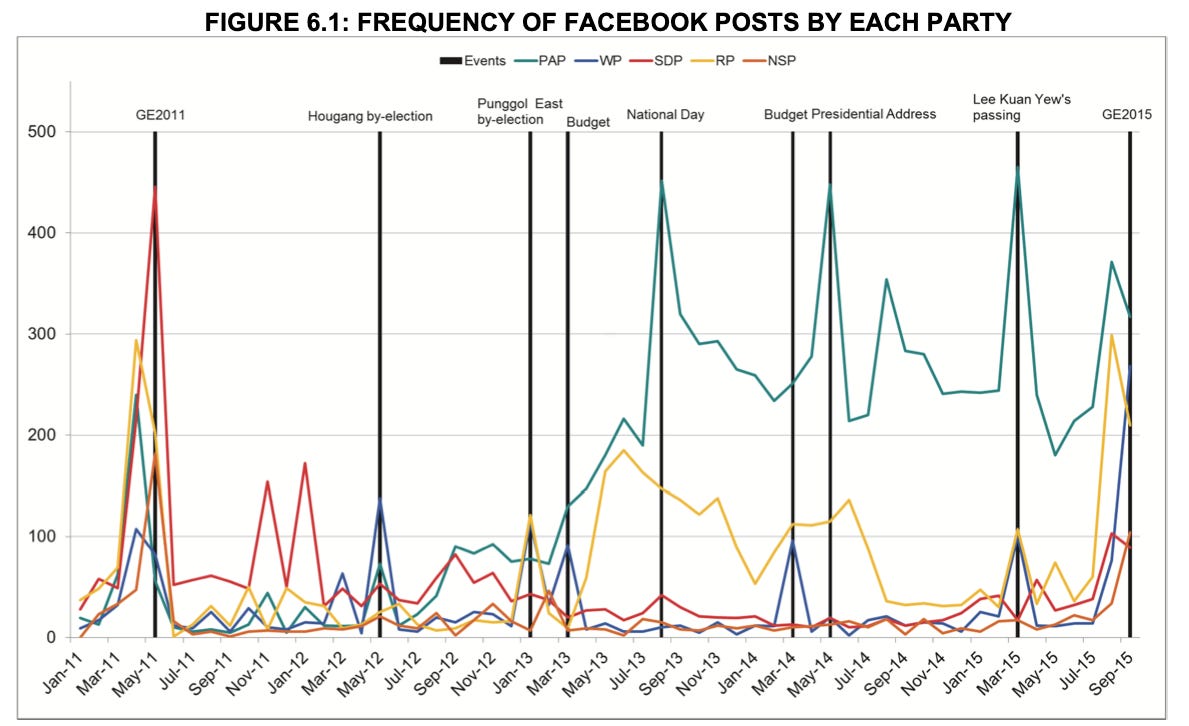

By that year though, the ruling party had already been upgrading its social media capabilities for some time. Just how much ground it made up was made clear by a study from the Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) released after the 2015 general election. It is worth reading in full as it contains a wealth of information, and I found this to be the most illuminating chart:

The giant awakens. Chart from page 103 of the IPS study “Media and Internet Use During General Election 2015”.

From the chart, you can see that the PAP started ramping up its Facebook use after the 2012 Hougang by-election, but its social media machinery really kicked into high gear after the 2013 Punggol East by-election. In addition to losing both by-elections, the party had also in 2011 scored its lowest vote share in a general election - 60.1 per cent - since independence.

The 2013 Punggol East by-election was the last time the Workers’ Party, or any other party for that matter, out-posted the PAP on Facebook.

Like what you’re reading so far? Sign up so you don’t miss the next update of Art Science Millennial!

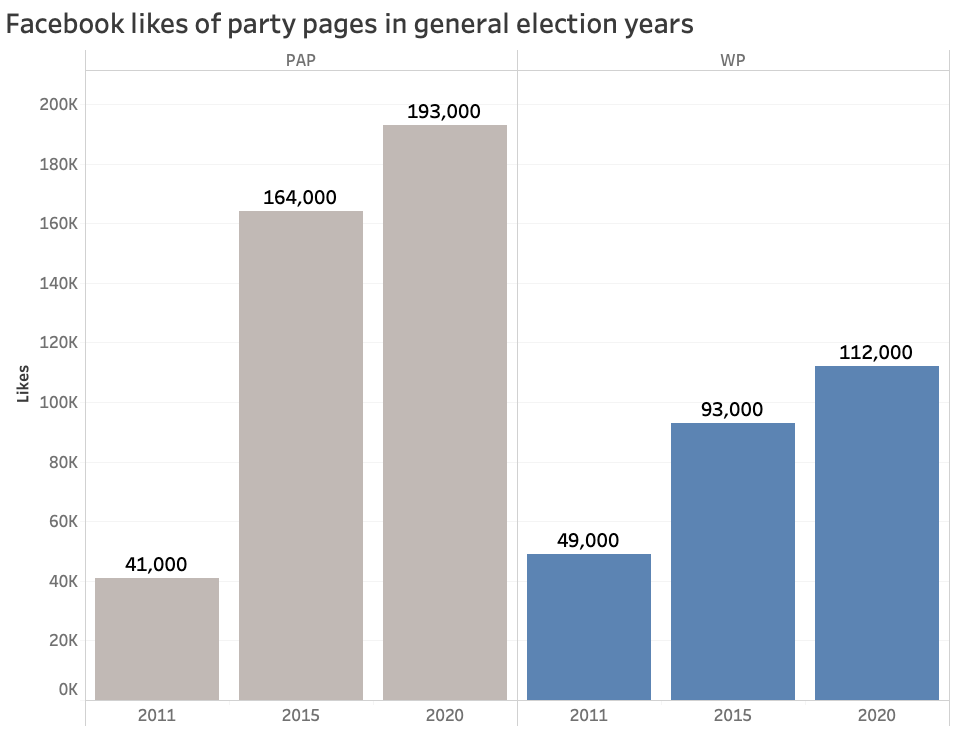

The number of likes on party Facebook pages also saw dramatic changes. Although the WP’s likes nearly doubled between 2011 and 2015, the PAP’s spiked fourfold. Growth has since slowed for both parties but the WP now has just 60 per cent of the PAP’s numbers.

PAP’s growth spurt left WP in the dust and the opposition party is nowhere near catching up today. 2011 and 2015 numbers from the IPS report, while I’ve added 2020 numbers to reflect the present situation.

Check out any of the posts by PAP politicians today and you will see that the overwhelming majority of comments are positive. Pro-PAP groups not officially affiliated with the party have also been active for some years now, as noted in this 2015 report in The Straits Times:

Shortly after Parliament heard in July that the Electoral Boundaries Review Committee was formed - a precursor to the general election - a People's Action Party (PAP) supporter sprang into action to start a private Facebook group and invited like-minded people to join it.

Named Silent No More - a reference to the oft-mentioned silent majority that supports the PAP and no longer wants to remain quiet - its early members sought to amplify the party's voice on social media during the elections. And they did.

…

IPS senior research fellow Tan Tarn How sees the current online political discourse as one that is "more reflective of the ground". He said: "There is now a spectrum of views. In the 2011 elections, there was a bunching of anti-PAP sentiments."

The emergence of pro-PAP online spaces like Facebook groups Fabrications About The PAP and Fabrications Led By Opposition Parties, and several neutral online outfits, has also gone some way to normalise online political chatter.

"This is good for the ruling party because it dilutes the anti-establishment sentiments," he said.

Now, I know there’s a lively debate over how many of these voices are part of the “Internet Brigade”, but the basic point remains - the ruling party has been able to project its presence and strength in cyberspace for some time now.

The PAP also has the budget to grow its social media usage in both volume and sophistication this election. In 2015, it outspent the opposition by 3 times ($2.16 per voter vs 73 cents). Here are some of its social media related spending that was reported:

Tampines GRC

PAP team - Fees for training and consultation on social media: (by each candidate) $2,250

…

The PAP also paid about $1,500 for "influencer engagement", which the party's executive director and Marsiling-Yew Tee GRC MP Alex Yam said were payments for a "long-term public relations consultant who helps to generate ad hoc content for our Facebook page".

When social media first gained prominence, it was the realm of the underdogs, who adroitly used it to bypass traditional means of communications. But as we’ve seen in recent years, the authorities across the world have grown increasingly adept at using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and other platforms as well. Social media doesn’t inherently favour one side or the other. Any group with the will can harness the technology towards its own purpose.

I’d love to know what you think of this newsletter and what you’d like me to write about. You can reach me at zi.liang.chong@gmail.com or by leaving a comment if you’re reading this on the Art Science Millennial website. If you enjoyed this piece, sign up so you get subsequent updates in your inbox!