A new era in SG politics! Or just overfitting data?

Getting lost in the weeds of the results can lead us away from the big picture

Welcome to Art Science Millennial, a newsletter for non-techies navigating the world of tech! I know the struggle because I’m one of you.

It’s been a month since the July 10 general election and the deluge of columns, op-eds, and think pieces analysing the outcome have mostly arrived at a consensus: This was a watershed election that heralded the rise of the young voter.

Reading these commentaries, I felt an acute sense of deja vu, like I’ve seen this movie before. And true enough, a quick Google search rustled up reports and analyses written in the immediate aftermath of the 2011 general election that reached a remarkably similar conclusion: It was a watershed election that heralded the rise of the young voter.

This is not to knock the work of journalists. After all, they are writing the first draft of history and trying to make sense of recent events that may still be unfolding. As a former reporter, I’ve contributed my fair share to this genre of articles as well.

Rather, this glitch-in-the-matrix moment resembles a problem that data scientists encounter when reacting too much to every piece of information — an issue known as overfitting.

What is overfitting?

Anyone who did physics in secondary school will remember doing something like this in class:

An actual O-level physics practical guide.

That straight line, called the line of best fit, captures the general trend that we can deduce from the data points (the small crosses on the graph). The inevitable question that comes next is: If it’s “best fit” we are after, why not a line that passes through every data point?

For instance, if you were plotting the relationship between the distance of your taxi rides and the fares you paid, you could draw this line:

You know at least one person (probably yourself) who drew this squiggly line during physics class. I know I did.

The squiggly line is an even better representation of how taxi fares changes with journey distance, right?

Wrong. Recognise that these taxi rides you took are just a drop in the ocean of the immensely larger number of taxi rides taken by everyone in Singapore. Indeed, if you took another bunch of taxi rides, you would probably find that the squiggly line doesn’t represent those new rides too well. A straight best fit line doesn’t pass through any data points, but it does a better job representing all of them, old and new.

Don’t get lost in the weeds by overreacting to every single data point.

In other words, the squiggly line overfits your original data. The best fit line encapsulates the general relationship between your variables (in this case, distance of journey and taxi fare). Therefore, it must represent not just the data you happened to have collected, but also all the data you didn’t get to observe.

Like what you’re reading so far? Sign up so you don’t miss the next update of Art Science Millennial!

Information overload

What does this trip down memory lane have to do with the elections? The People’s Action Party’s (PAP) national vote share is always heavily scrutinised for what it says about Singapore’s direction and the message voters are trying to send. Again, there is merit to such analysis but we run the risk of reading too much into every shift and declaring a new epoch each time something dramatic occurs.

Looking at the general elections from the last 30 years, when either Goh Chok Tong or Lee Hsien Loong was prime minister, we get a roller coaster of political twists and turns:

The squiggly line resurfaces.

Adopt the approach of a best fit line, however, and we get a broader perspective:

Yes, the best fit line doesn’t always have to be a straight line.

The zig-zags of overfitting show fickle voters vacillating between the status quo and change, with each spike and slide seemingly imbued with vast implications.

The best fit line tells the story of a cautious electorate that is taking small, tentative steps towards parliamentary diversity and will apply the brakes if the pace of change exceeds its narrow comfort zone. Indeed, this is an electorate that grew the number of elected opposition MPs from four to 10 — with a dip to two in between — over three decades. For further context, that’s going from 4.9 per cent of elected seats in 1991 to 10.8 per cent in 2020 — certainly more evolution than revolution.

Two sides of the same coin providing vastly different vantage points.

Seeing things that aren’t there

If charts and graphs aren’t your thing, just remember: Overfitting occurs when we read too much into data and ascribe meaning where there is none, mistaking random noise for a sign that we’re onto something.

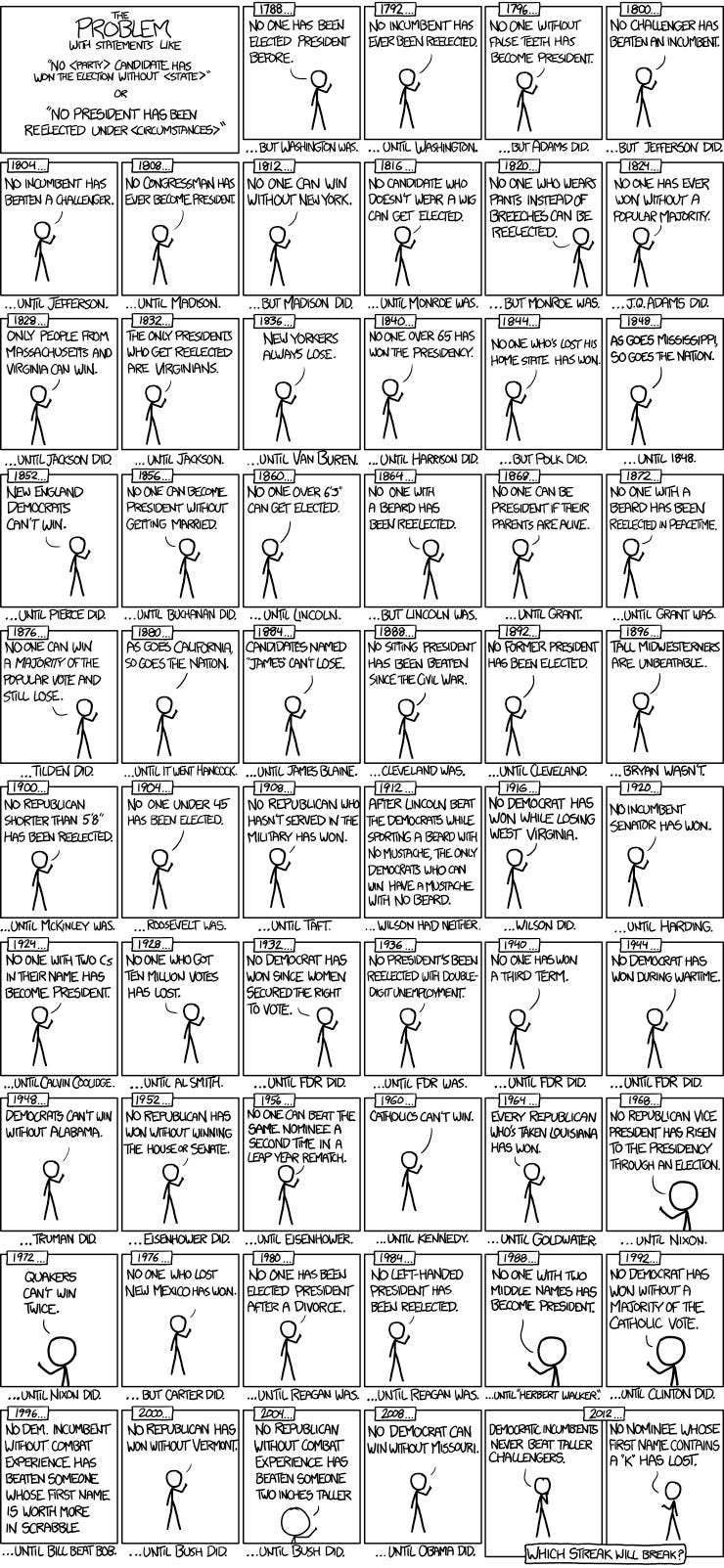

We are prone to overfitting because humans have a tendency to seek out patterns when we take in the world around us (hey, that cloud looks like a rabbit!). This comic neatly illustrates how in the search for trends, we may inadvertently misconstrue coincidence as highly significant precedence:

Source: xkcd

One of my favourite examples of phantom trends is the belief that people in the western parts of Singapore are more supportive of the ruling party than those in the east. (At this point, east siders who happen to be opposition supporters will crow that their side of the island is just better at everything.)

It is true that the PAP has won several constituencies in the west by handsome margins of victories in the past few general elections. But it doesn’t automatically follow that voters living in west Singapore are somehow more predisposed towards the PAP. After all, one of the four seats the opposition won in 1991 was in the west. The opposition candidate for Bukit Gombak even beat an acting minister, the first time a cabinet member was unseated in Singapore.

This year’s election also provides a timelier reminder. The PAP clung on to West Coast GRC by the skin of its teeth, with its winning margin smaller than the number of rejected votes and people who did not vote put together. It also had close calls in Bukit Batok and Bukit Panjang, constituencies in the west. Looking at a map of the full results, it’s clear that candidate quality is a better indicator of the opposition’s performance in any particular constituency than geography.

Finding a good fit in our lives

As with most concepts discussed in this newsletter, overfitting is not just applicable to politics and data science. When faced with an intractable issue in life, it’s worth taking a step back and considering if the problem is caused by overfitting.

Having trouble making a decision? Trim your list of pros and cons down to the top factors instead of agonising over every aspect.

Can’t make sense of something? Maybe you’re getting bogged down in the details and missing the big picture.

Think you got it all figured out? Check if you’re shoehorning the data to match your theory.

A good rule of thumb: The more elements you take into consideration (data scientists call this model complexity), the higher the chances of overfitting.

I’d love to know what you think of this newsletter and what you’d like me to write about. You can reach me at zi.liang.chong@gmail.com or by leaving a comment if you’re reading this on the Art Science Millennial website. If you enjoyed this piece, sign up so you get subsequent updates in your inbox!